Part 3: “Strengthening Your Strategy”

Part 3: “Strengthening Your Strategy”

This series has been designed to help CISOs and other risk management practitioners examine their programs from a unique perspective – one in which the objective problem your organisation is trying to solve takes center stage and risk managers can effectively respond as that problem morphs over time.

This is the third of a four part series.

Click here to read Part 1 or Part 2.

How Do You Make the Most

of Continuous Monitoring?

The vagaries of program building:

To effectively reduce the uncertainty and potential impact of third party risk, every program must efficiently integrate the complex landscape of people, processes and technology. You cannot simply expect that your program will be humming along and proficient in six months.

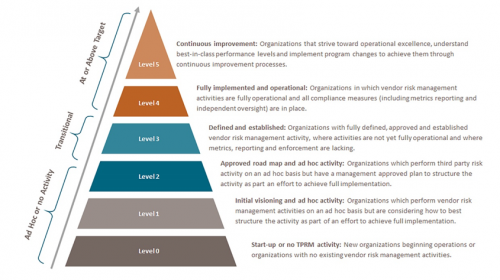

TPRM programs require management of layered complexities, with dependencies and interdependencies that range from the need for specialised workforce engagement and retention, to socioeconomic and geolocation concerns, to legal and regulatory compliance. This complexity extends beyond your program’s control to factors that are under the control of other business units within your organisation, as well as those controlled by your third parties and their subcontractors (nth parties). A mature Third Party Risk Management (TPRM) program goes well beyond regulatory compliance.

Figure: What a mature TPRM program looks like [1]

Figure: What a mature TPRM program looks like [1]

So, how can you get your program from where you are to where it needs to go, so that you can gain greater insight and better manage the risks your organisation faces every day?

From the ground up, it is essential that all business units and functions have a seat at the table when it comes to designing, executing, and improving your program. This means it is important to engage with representatives from procurement, risk, legal, internal audit, and all other stakeholders in aligning the program’s design with company goals. As you educate stakeholders on what you are trying to achieve in your TPRM program, you can collectively set expectations that meet the everyone’s needs, gaining greater buy-in that can translate to higher levels of program maturity over time.

Building your strategy:

Strategy and tactics work in tandem and should not be confused. “Strategy defines the organisation’s risk management goals; the tactics are the means by which those goals are achieved.”[2]

A trap is set if you believe you can follow your tactical process steps and come out the other end of the funnel with strategic success. There is a need to align your tactics to your organisation’s culture, processes, rules, expectations, measurable objectives, and other relevant needs.

Your strategy should document your TPRM program goals and measurable objectives, both of which need to be in line with your organisation’s overall risk management goals.

Your tactics will be the tasks and processes you will use to achieve those strategic goals.

However, in the execution of the tasks and processes, TPRM professionals often lose sight of the need to adapt their tactics to stay aligned with strategy. To gain any measure of agility in risk management, tactics need to be regularly adjusted based on information gathered from your management experience – i.e., what works and what doesn’t work.

Continuous monitoring – separating fact from fiction:

What is continuous monitoring really? It is a nascent tactical solution that is gaining traction globally with outsourcers. In some regulatory environments, it has recently become a required part of TPRM programs.[3] Everyone is talking about continuous monitoring – looking at their vendors in real time hoping to better understand the risk these vendor relationships pose.

The problem of using continuous monitoring to ensure that your tactical solutions will accomplish your goals gets ever more complicated due to the variety of demands – legal, geopolitical, socioeconomic, workforce skills and other demands – that compete for attention. In the real world, no one solution provider can possibly cover all these areas of expertise.

There are multiple components that need to be considered in order to demonstrate value in a continuous monitoring score, or the lack thereof. To have data that is reliable, accurate, and predictive, you need to know:

- exactly what data is being deemed “on a continual basis” and used to effect a change to the score,

- how accurate that data is,

- whether the resulting score has a useful level of precision that would indicate that any daily score fluctuations are in fact useful indicators for the consumer of that continuous monitoring report, AND

- how that data relates to your organisation’s goals and objectives.

Monitoring efforts may be designed around something that is “required” and “expected” to make people feel safer. However, that can be misleading. If you take a third party’s continuous monitoring score, it can change over time, sometimes quickly and without sufficient accuracy or precision to be useful for risk managers. In that case, the scores provide only the illusion of meaningful insight into that third party’s security posture – what Bruce Schneier calls “security theater” – without doing anything to reduce the uncertainty surrounding a third party’s risk ecosystem.[4]

Continuous monitoring is perceived as literal, real time data processing. However, the data used for continuous monitoring is more likely cyclical over a time period that is not instantaneous, e.g., updated over a cycle of 4 hours, days, or even weeks. Many definitions focus on security feed and monitoring – and make people simply feel safer, rather than protecting them more effectively. Not all data is available or easy to monitor in real time. For example:

Domain Name Registry data can be viewed in a “continuous” feed, but in reality that data is only updated once every four hours (or less). In this case, every four hours would constitute “continuous” since that is its level of availability.

Breach notification data is not real time and cannot be continuously monitored. Notification happens (by definition) after the fact. When a provider is breached that had provided a service to a large number of companies, there is a period of time between when the actual breach occurs and when public notification of that breach is made. During that interim time period, the customers of the vendor are notified as part of the incident management and notification process. However, a continuous monitoring service provider does not receive the breach notification until the it is made public. So, the continuous monitoring feed provision of breach notification is a delayed piece of “after the fact” information, which lowers the value of that notification.

Accuracy versus precision:

Continuous monitoring vendors provide a scorecard or other ranked value, which the continuous monitoring vendor believes depicts the risk a given third party poses to your organisation. Some of those scores are extremely precise, but very inaccurate.

For example, suppose your spouse/partner asks you what time you will be home for dinner, and your response is 6:00 pm. That is a very precise piece of data. But if you arrive home at 6:20, that precision was not very accurate, nor was it useful. We know there are many factors in determining what time you will actually arrive at home, things such as workload, traffic, unexpected interruptions, etc., but you could look back over time and use data to determine that in reality you usually arrive between 5:55 and 6:45, with the average arrival time of 6:15. Instead of being precise, you may want to respond that you will be home between 6:00 and 6:30, thus improving your accuracy and decreasing the uncertainty of your actual arrival time, which would prove a more useful estimate for your spouse/partner. You could also say between 4:00 and 9:00 pm, which is very accurate, but no has useful level of precision for planning purposes.

In the world of continuous monitoring, score ranges, such as 0-10, 1-100, 1-1000 are used. Let’s assume the value range under consideration is 0-10, calculated to two decimal places. You achieve a score of 4.75, which is extremely precise. But four hours later, new information changes that score to 4.76 – again extremely precise. However, the change is virtually meaningless, because it does not help you understand what’s really happening.

Let’s go one step further. Let’s say that the change is score is significant, going from 4.75 to a 1.25. This is significant enough to be called a trigger event. In your tactical processes, you need to have a plan in place ahead of time that defines what triggers are based upon and what your plan of action is when a trigger event occurs with one of your vendors.

Getting better accuracy:

Compound these examples using proprietary scoring methodology that are not transparent in their analysis and now the uncertainty around how precise and accurate that score actually is increases. Add more uncertainty to the equation as the incoming continuous monitoring data fluctuates, and it becomes difficult to understand just how much risk that vendor poses to your organisation. The usefulness of the score drops even further if you don’t have an understanding of the quantitative risk in that particular vendor relationship.

A better way to attain a more suitable picture is to provide a grade (score) with a useful degree of precision, based on accurate, relevant data, that is calculated by an open source community-tested methodology that allows you, the end user of the data, to align that information with your own organisation’s unique defined risk appetite. That approach provides real relevancy to a score, which gives meaningful intelligence that can be used to reduce the uncertainty of the potential risk posed by that vendor.

Reducing churn:

In the world of continuous monitoring, information churn is created when data is collected and reported that does not relate to your organisation’s risk management needs. If your actions are based on information that is poorly aligned with your TPRM goals, sooner or later you’ll find that your actions are not yielding results that are in keeping with your organisation’s needs. You will experience churn, ill-advised decisions, and wasted effort.

At some point, your organisation will have to understand whether the information it receives can be acted upon in a way that is aligned with its own unique needs. You need to ask, “how was that score derived?” If your continuous monitoring solution has a proprietary, non-transparent algorithm (i.e., a black box), you have to be willing to accept the score without know the answer to that question.

In a real world example, a vendor was identified as being on the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) list, which restricts by regulatory mandate the use of specific vendors for a specific service or services. The outsourcer used this alert as a trigger and launched a response, which in turn created significant churn. Instead, the outsourcer could have reduced churn in two ways. First, the outsourcer could have determined this was a single source vendor, so the use of this third party remained important. Second, the outsourcer could have determined if the service listed was one for which that third party was contracted. If not, then the OFAC alert could be flagged for future reference as not reflecting the outsourcer’s risk management requirements.

In this case, the vendor’s listing on OFAC constituted a continuous monitoring alert, so the company performed a quantitative analysis and determined there was little to no risk, unless the OFAC service was used. To reduce churn over time in this type of situation, the continuous monitoring score needs to able to automatically reflect that the OFAC score does not reflect the outsourcer’s business needs, and that factor needs to be updated if that status changes for any reason.

Recommendations:

Know your mission – to reduce the uncertainty around the risk exposure in the most cost effective manner that you can – and stick with it.

You can plan for a higher level of success by underpinning your tactics with a standardised, industry-vetted program model, such as the Shared Assessments Program. You can also make sure that your workforce speaks the business language of risk and business impact, which most do not.

To build a more successful process:

- Define your mission.

- Align your strategy to that mission.

- Base your tactical processes with that strategy in view.

- Use the OODA Loop (Observe-Orient-Decide-Act) to guide your tactical processes.

- On a regular basis, based on your OODA experiences, measure and document the improvements that you make to your tactics.

The combination of a strong set of tools and a robust understanding of impact will naturally lead to the understanding that you cannot just flip a switch and have a mature TPRM program. Building a robust program takes quantitative analysis, careful integration of data into your processes, and a vision that includes a step process for improvement over time. Resources are available that can help guide your quantitative analysis, including the Factor Analysis of Information Risk (FAIR) Model approach to risk analysis.

Pay attention to staying on-mission – don’t get bogged down in tactical complexities – instead focus on your strategic clarity. Your tactics should morph over time, driven by the results achieved from those tactics. Tactics should be driven by your strategy, rather than falling into the trap of thinking that you are achieving your strategic goals just by executing tactics that may be falling short of your strategic goals.

Next Steps:

The first three articles in this series covered:

1) Examining your TPRM program’s objectives,

2) Understanding the conditions that create third party risk, and

The final article in this series will discuss optimisation of your assessment efforts, contracts, and treating your third parties as trusted, valued partners.

About the Author

Bob Maley, CTPRP, CRISC Chief Security Officer, NormShield Cybersecurity is an award winning senior leader in information security and a strategic thinker with experience as an information security strategist designing and building information security programs for PayPal Holdings, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and for the healthcare sector.

[1] Vendor Risk Management Maturity Model (VRMMM) Program Maturity Levels. The Santa Fe Group, Shared Assessments Program. 2019. Reprinted with Permission.

[2] Innovations in Third Party Continuous Monitoring: With a Name Like OODA, How Hard Can It Be? The Santa Fe Group, Shared Assessments Program. 2018.

[3] Examples of industry-specific guidelines for monitoring governance include European Banking Authority Updated Guidelines on outsourcing arrangements. EBA. February 2019; AT 9 Outsourcing. August 15, 2013. Germany’s Federal Financial Supervisory Authority (BaFin); Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2015/35. October 10, 2014. Official Journal of the European Union. January 17, 2015; Cybersecurity Legal Task Force Vendor Contracting Project: Cybersecurity Checklist. American Bar Association (ABA). November 2016; European Union (EU) Regulation 2016/679, better known as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). April 14, 2016. Effective May 2018. EU Parliament; FFIEC Information Technology Examination Handbook. Appendix J: Strengthening the Resilience of Outsourced Technology Services. FFIEC. February 2015; New York State Department of Financial Services cybersecurity regulation 23 NY CRR500. New York State Department of Financial Service. March 2017; Outsourcing Risk Management. Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS), March 2013; SYSC 8.1 General Outsourcing Requirements. May 2016. United Kingdom’s Financial Conduct Authority (FCA); Third-Party Relationship: Supplemental Examination Procedures Bulletin. OCC 2017-7. January 2017; OCC Advisory Letter 2000-9; February 2015; Third-Party Relationships: Risk Management Guidance. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC). OCC Bulletin 2013-29. October 30, 2013; Third-Party Relationships: Risk Management Principles. OCC Bulletin 2001-47. Adapted from The Santa Fe Group, Shared Assessment Program. 2019.

[4] Schneir, B. Beyond Fear: Thinking Sensibly about Security in an Uncertain World. 2003. Copernicus Books. https://www.schneier.com/books/beyond_fear/